352project

Game for EECS352 by Chloe, Kat, and Jack

Project maintained by chloemb Hosted on GitHub Pages — Theme by mattgraham

Cosmic Scale

Final project for EECS 352

Taught by Bryan Pardo at Northwestern University

Chloe Brown | chloebrown2020@u.northwestern.edu

Katrina Parekh | katrinaparekh2020@u.northwestern.edu

Jack Warshaw | jackwarshaw2020@u.northwestern.edu

Click above to see a demo of Cosmic Space’s gameplay.

Click here to view our poster for the presentation.

PROJECT SUMMARY

Our goal for this project was to create a simple runner game wherein the player can control their avatar with the pitch of their voice. We aimed above all to create a fun, responsive, challenging game. The nature of the game also means that those with motor disadvantages (ie, shaky hands or poor coordination) can still play.

In order to make the game work for all human vocal ranges (and even some instrument ones), the game calibrates before each play instance by asking the user to make a low pitch and then a high pitch. Then, as the game plays, it takes input from a microphone, detects the pitch of the input in real time, and translates that pitch to a position on the game screen logarithmically relative to the calibrated low and high pitches. The player's avatar follows that position, allowing real-time input based on pitch.

We coded this game using Python 3.7 with the pyaudio, aubio, and pygame packages. Pyaudio allows us to take input from a microphone as a stream, while aubio allows us to detect the pitch in real time. Pygame is a Python library for making games in Python. We picked these packages because they work together in a Python environment, allowing us to integrate them seamlessly with one another.

A screenshot from the in-game window. The rocket on the left is controlled by the pitch of the player’s voice.

PROJECT DISCUSSION

Because of Cosmic Scale's real-time pitch detection, we are unable to extensively process the input stream. This means we had to pick the modifications we made to aubio's pitch detection output very carefully. Our raw pitch detection ouputs a constant stream of numbers corresponding to the frequency the microphone input is detecting. When there is no sound detected, the output is zero. We don't want the player avatar to move down on the screen whenever the player stops to take a breath, so whenever the pitch ouput is zero, we instead keep the player at the position that it was last.

Additionally, Cosmic Scale's input detection functions best in an environment where there is little to no background noise, because background noise can be picked up by the microphone and cause the player avatar move erratically. To partially mitigate this problem, we have imposed a minimum volume threshold on the input passing. However, this method does not work perfectly as loud or sudden background noises can still be picked up by the microphone.

In the future, we believe it would be interesting to implement speech recognition in the game's menus so it could truly be a hands-free experience. This would allow even more people to play Cosmic Scale.

WINDOWS INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS

To install and play Cosmic Scale on your Windows machine, navigate to the GitHub repository linked at the top of this page. Download and unzip the files, then double click on the install.bat file to install the required packages. After this, you should be able to double click the CosmicScale.bat file to play Cosmic Scale.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

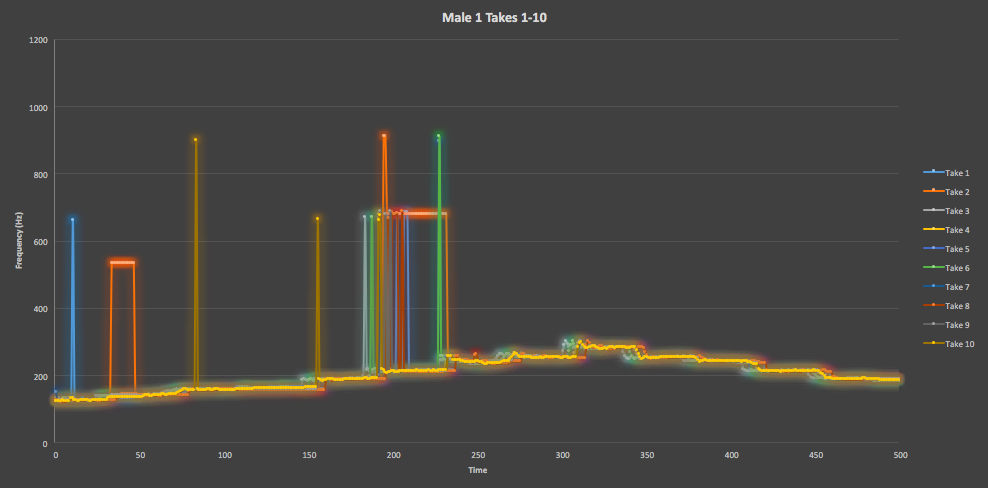

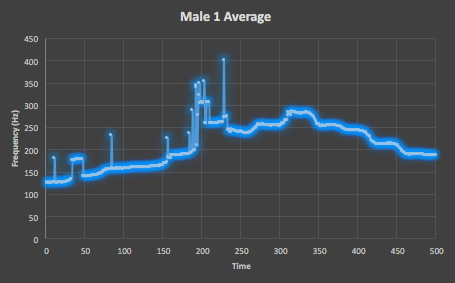

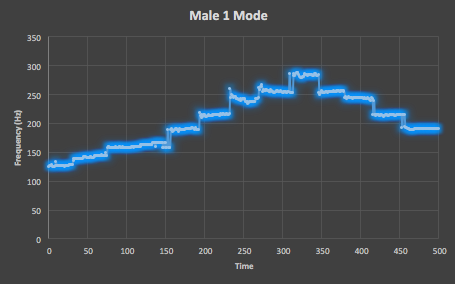

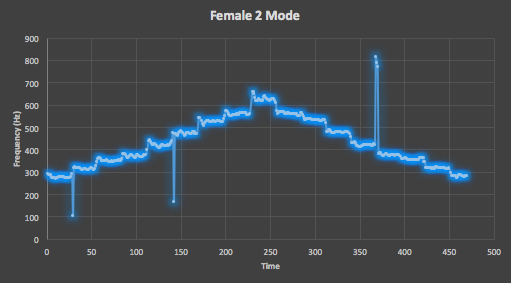

In order to analyze the performance of our pitch detection through aubio, we used the dataset of VocalSet, which contains actual singing in a variety of methods by several different singers. We used this dataset for the diversity of testing that it allowed us to choose from, and ultimately decided on using both male and female voices for straight A scales. We used the straight a scales for male_1, male_2, female_1, and female_2, and took 10 samples of each voice, recording with the same method each time for consistency. Overall, we found that the pitch processing worked fairly well, as each singer's mean and mode tracks ended up maintaining the same rough shape of their component recordings. Though the mean and mode of the tracks are both fairly accurate, we found the mode to follow the shape of a scale better than the mean, and have based our assesment mainly on those. We decided to use scales for testing over the other singing techniques presented by this database because we believed its data visualizations would be the most recognizable and would stretch a wide range of singing values.

In terms of possible errors for data collection, one may be the the technique used to get this testing data. The testing data was collected manually, meaning that the speaker quality will impact the pitch detection based on well how the microphone can intake the range and quality of sound output. Additionally, because the process was done manually, there is some error based on holding up the microphone directly to the speaker as it was not in exactly the same location each time. Overall these problems could be solved through automated testing, though these tests were manual because we wanted to test in the same way that we were taking in data, through the speakers, and automated testing would've had to have been directly through file stream inputs. The files used for testing can be found here.

Figure 1. Here is an overlay of all 10 testing takes of the Male One straight scale track from VocalSet, showing a high degree of similarity across each recording with some variation confined to areas of large spikes.

Figure 2. Here is the average value of all 10 testing takes of the Male One straight scale track from VocalSet, which shows a fairly unifrom scale with some unexpected variation between 200 and 250 that breaks this uniformity.

Figure 3. Here is the mode of all 10 testing takes of the Male One straight scale track from VocalSet, which shows an extemely uniform distribution of values along the expected scale shape.

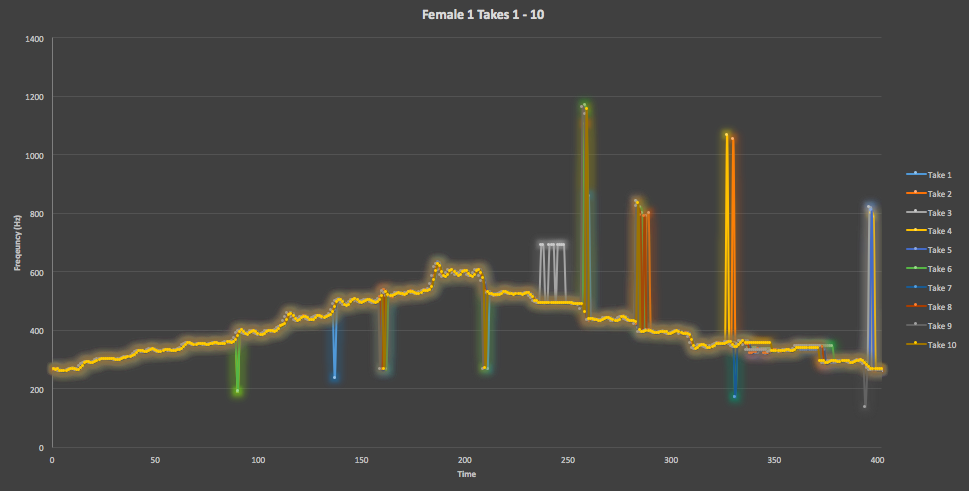

Figure 4. Here is an overlay of all 10 testing takes of the Female One straight scale track from VocalSet, showing a high degree of similarity across each recording. Though there still are a decent number of occassional spikes, one of the spikes occurs at the same for each track, showing that our pitch detection is noticing this variation that likely occured due to the singer.

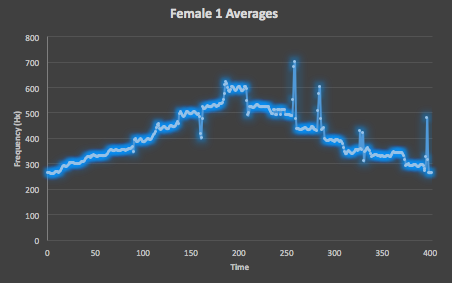

Figure 5. Here is the average of all 10 testing takes of the Female One straight scale track from VocalSet, which shows a uniform distribution of values along the expected scale shape and significantly fewer unintended spikes.

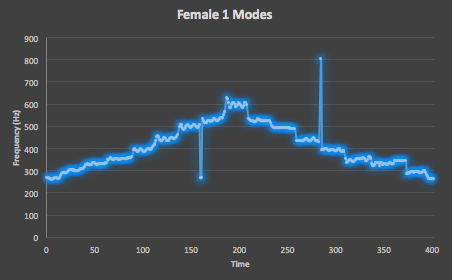

Figure 6. Here is the mode of all 10 testing takes of the Female One straight scale track from VocalSet, which shows an extremely uniform distribution of values along the expected scale shape, with only one unintended spike.

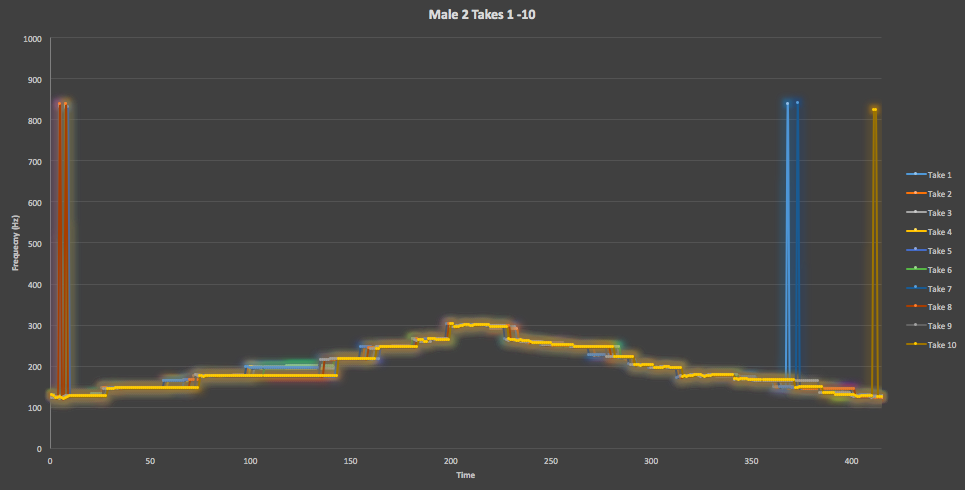

Figure 7. Here is an overlay of all 10 takes of the Male Two straight scale track from VocalSet, which shows some slight variation from the expected scale shape but also presents very few unintended spikes.

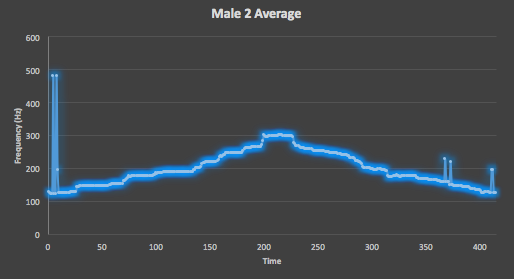

Figure 8. Here is the average of all 10 testing takes of the Male Two straight scale track from VocalSet, which shows a reduction in the size of unintended spikes and a tightening into the expected scale shape.

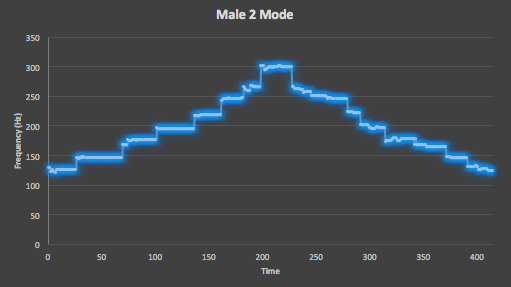

Figure 9. Here is the mode of all 10 testing takes of the Male Two straight scale track from VocalSet, which shows a nullification of unintended spikes and the expected scale shape, but also the loss of a few expected regions of intended spiking.

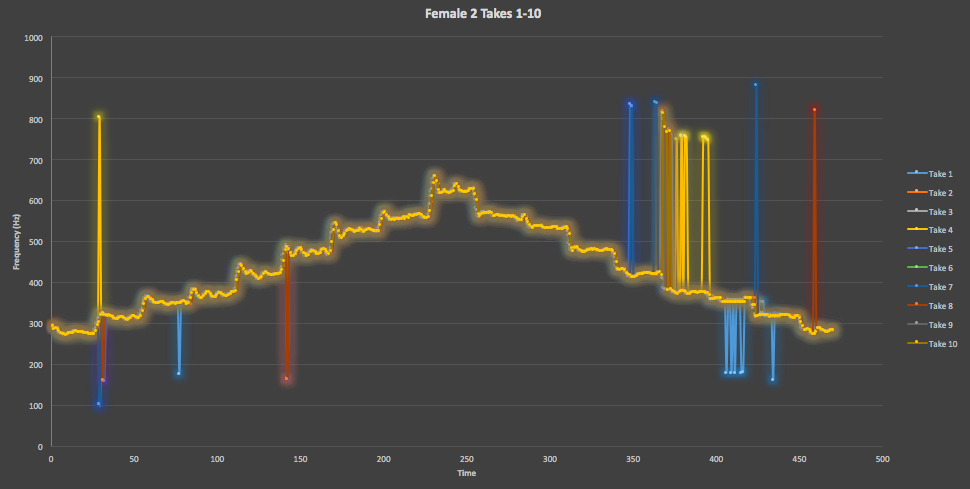

Figure 10. Here is an overlay of all 10 testing takes of the Female Two straight scale track from VocalSet, which shows a decent overall scale shape that fits as expected, but a decent number of unintended spikes in addition to several intended ones.

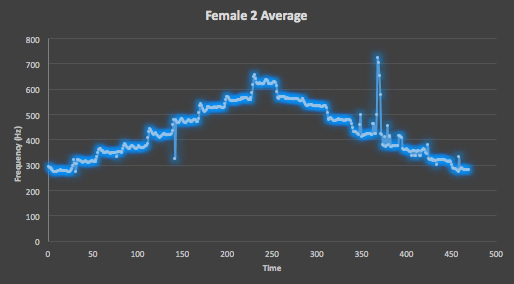

Figure 11. Here is the average of all 10 testing takes of the Female Two straight scale track from VocalSet, which shows a dramatic reduction in some of the more isolated unintended spikes will retaining regions heavy with intended and unintended spikes, as well as a fairly tight scale shape that still has some variation.

Figure 12. Here is the mode of all the 10 testing takes of the Female Two straight scale track from VocalSet, which shows an extreme tightening into the expected scale shape, with a reduction of the number of intended and unintended spikes across the track, though the size of the ones present is not lessened as it was for the averages.